At first there were just a few, dark spectre-like shadows silhouetted against the deep blue, floating. And then, some minutes later, several more flitted into my line of vision. Cloaked almost entirely in black, menacing, circling in effortless formation hundreds of metres above me; and higher still, by another hundred metres or so, several more in a holding pattern, soaring on thermals. And, farther westward, fading to specks into the haze of the distant horizon, I count dozens more. All of them seeking the dead and on watch for the dying.

I am taking my rest – at the highest point in Barichara, a sleepy colonial town in the north of Colombia – in the quaint if idiosyncratic Parque Para Las Artes, a little park of pretty flowers and sculptured artworks and several small ponds, all of which are dry and a bit forlorn, the rainy season still months away. I am under the gratifying shade of a leafy tree and gazing through its interstices at the deep blue beyond. And at the soaring vultures, majestic and graceful harbingers of death, holding vigil across this endless valley of scented flowers and mountains reaching high to brush against the clouds. You can stop life here or at least pause for a moment or two and reflect upon the now and then and slip into the mood of the place, supremely unhurried. Not much seems to happen here and that, at least to my sensibilities, is precisely its appeal. The town is perched upon a high plateau, on its northern side, in fact in all directions from the Parque Para Las Artes, it overlooks a magnificent valley of jagged mountains, rolling hills, and fertile farmlands. And had Barichara been on the banks of a river of a distant past, in a long-ago age when everything was so new that places had no names, it could have been that ancient and storied town of mirrors, Macondo, its streets echoing with the cries of the descendants of the Buendía family lamenting its many misfortunes and a hundred years of solitude.

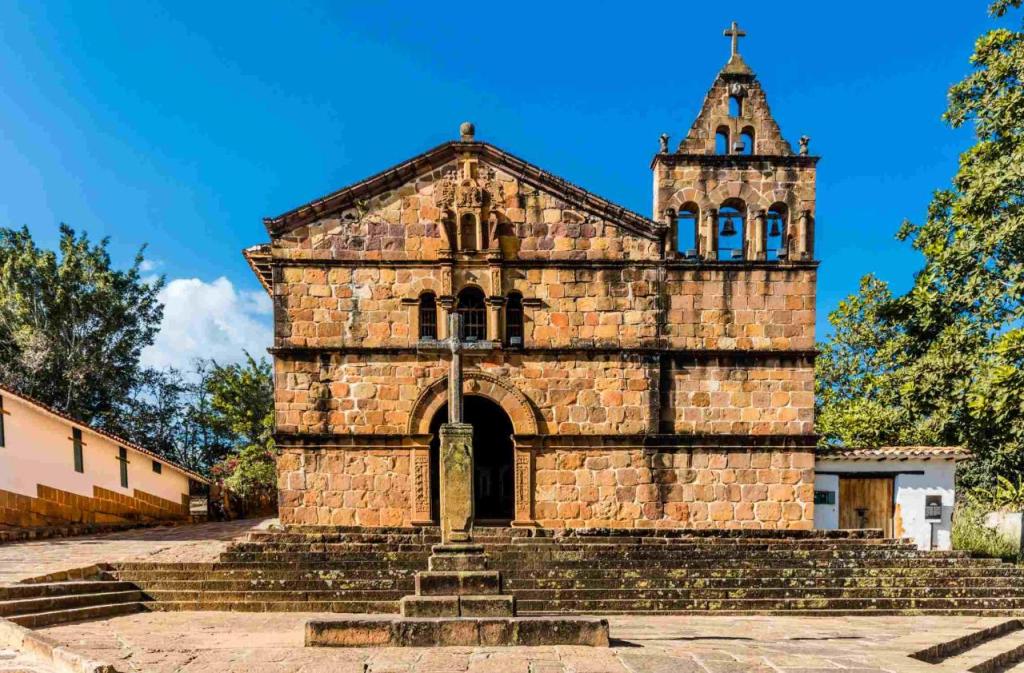

The lamentations I do hear, a scratchy vinyl, an aria it sounds like, seem to come from the church nearby, one of several in this town of a few thousand souls. And, look, there is a river, the Suarez River, barely visible several hundred metres below my vantage point, a sinuous mass of surging whitewater coursing across the valley floor and disappearing into the dark green bend of the canyon. But of mirrors, I see none.

It’s a small town, Barichara, arrived at via a winding vertiginous road, about forty minutes from the town of San Gill. My arrival here, after a lurching ride atop a high seat in a minivan with no working seatbelts, I think of as a small blessing. How the driver avoided careening into the mountainous abyss notwithstanding numerous opportunities I shall never know. And it is a relief to dismount, slightly nauseous, but eminently grateful to have feet firmly on ground. The driver and I exchange looks, he gives me a nod, and drifts off with a cigarette.

Barichara’s streets are neatly laid out in grids and spotlessly clean. It is I am told, save for some reconstruction work in the late 1970s, more or less unchanged since its founding by Spanish conquistadores some three hundred years ago. Whatever the case Barichara looks to have weathered the passage of centuries with considerable grace and probably a degree of good fortune given this country’s bloodied history, both recent and days long past. The fact that the town serves as a regular backdrop to Spanish-language films and those ubiquitous telenovelas in no way detracts from its charms. I wonder, also, at its claim to be one of the prettiest towns in all of Colombia, a claim I am unable to credit, my frame of reference limited mainly to Bogota, a dreadfully crowded equatorial city which, during my visit, was forever wet, the rains often and torrential leaving me cold and miserable and sodden. But Bogota, just over 300 km to the south, is worlds away. And Barichara – yes, she is indeed very pretty – has a quiet and languid charm inducing idleness in many a soul passing through its narrow stone-cobbled streets, some of the steepest I have encountered. Glute-busting and exhausting, which is why I am here in the now and reflecting upon the then, at ease on my back, watching vultures, and finding it difficult to break my respite?

To leave the shade is to invite the heat, unrelenting and exhausting and searing. The temperature on my mobile reads 31c, but it’s a deceptive 31c. It feels hotter, and it is hotter. Much hotter up here, high on the plateau, where the air is still and breezes sparse. Without meaning to I tune into a nearby conversation, a mix of visitors from faraway lands, contemplating the next stop in their itinerary. The cemetery, I overhear, is a visit deserving of some merit. Cemetery? I interject with a question and the group leader smiles, pausing for effect as if he had been waiting for just such a moment, and deadpans, “well, it’s not the most liveliest of places”. I smile too, not minding being an unwitting foil, understanding that the answer likely would have been the same no matter the question.

So, more out of an idleness of thought than any particular interest, I decide to wander after this eclectic group of strangers and am almost immediately filled with remorse for having left the shade. The heat is really quite extraordinary, and I slow to a crawl. The group, however, is undeterred and march onward with a purpose ill-fitting a place where life is unhurried. We descend to pass through the main square, bustling with tourists today, about fifty or so at most, but in the smallness of the square seem innumerably more. I notice also that many are taking their ease – relaxing in cafes or lounging in the lushly-treed garden in the centre of the square – wisely avoiding the heat. I make a mental note to pass this very way again, to stop for a gelato later or possibly sample a local delicacy, deep-fried hormigas Culonas (big-bottomed ants), and continue following the cemetery-bound group. (For the record, the ants are chewy, a bit sour, and definitely an acquired taste).

The trek to the Cementerio Barichara ends in disappointment. It’s closed for the day, but the sun is still bright in the western skies and streets filled with people. So, a long wilting trek up a steep hill comes to this – the dead need their siesta too. That to me seems a noble purpose and I repair to a nearby bench. From my vantage, by the arched iron gates, I can see into the cementerio and what I see are elaborate and ornate sculptures, homages to the departed, many decorated with bright plastic flowers and bearing witness to past lives, ordinary and some out of the ordinary, at least judging by the size of the tombstones, some of them several metres in height. It’s a crowded but neat yard, the tombstones cheek by jowl, the plastic flowers paling against the effervescent bougainvillea. There is a tombstone carved like a trunk of a felled tree; upon it hangs a sculpted white fedora and guitar leans against it, presumably a musician of some renown in a past life. There is even an artisan’s version of Gaudi’s Last Supper; and, of course, this being Latin America, there are many of Jesus of the Sacred Heart and of the Virgin Mary.

There is a solemnity in the air and in the drowsiness of the late afternoon I become aware that the streets are now quieter, thinned of the crowd, and I am alone here, taking my rest with the dead. And I realise also that this is it, really, for things to do in this village town. Yes, there are cafes and restaurants and markets, even a few art galleries, but visit any of the several churches, the Parque Para Las Artes, the cemetery, and then you are done. But physical beauty aside, there is an essence, something elusively deeper to this place. And, after almost three days of not doing much, I realise that what Barichara offers is really quite simple: an all-encompassing serenity, an interlude from the everyday of life. But serenity and reflection bring also the inescapable melancholia of memories – of moments lost and recaptured and lost again. But a moment is much more than just a moment; it is filled with the unending rhythms of life, all life. And so it is in Barichara, where the days are long and uneventful and unhurried, and filled with moments. One should not journey here to see things – true, there is much to please a facile observer – but to feel, feel its being and surrender to the mood of the place as you gaze over red-brown rooftops under skies streaking a dull orange and listen to the clip-clop of footfalls upon cobbled streets.

Night falls and the extraordinary heat of the day softens. The sounds and sights of the day merge into the sights and sounds of evening. Lights spill from open doorways and arched windows, children are still at play, their laughter and squeals punctuate the air, a most joyous sound. And, surely, a most life-affirming sound, a reminder of life’s wondrous possibilities. I cannot know for certain, but my sense is of a country eager to embrace a new world of being, a world without the sounds of gunfire and guerrilla warfare and death. This world of peace is still new here, imperfect, and there remain pockets of unrest, but peace seems to have taken an enduring and, yes, intoxicating hold. And at this particular moment, in the cool of this deepening evening, my thoughts turn to the past, to that distant afternoon when Colonel Aureliano Buendía faced a firing squad. His misfortunes were, of course, allegories for this country’s tormented history, and perhaps – just perhaps – if the Colonel had been here, in the now, a time of peace, the world may have never known his tale of lamentations and misfortunes and solitude. And that would have been an immeasurable loss for the past is what the past is even if Barichara, with all its restored glory of a colonial past, seems to recall only that it was once fabled and as ethereal as the orange-streaked skies of yet another glorious sunset.

Leave a comment